The 2014 Athens Marathon – ‘The Authentic’, as it is charmingly named (to distinguish it from all the inauthentic marathons out there?) – was my own first attempt at running 26.2 miles / 42.195 kilometers. Having witnessed the spectacle of the Athens marathon in 2013, the sight of runners well into their seventh and eighth decades doggedly making their way along the final 500 meters to the finish line inspired me to sign up as a motivation to get fit. I thought, “if I’m going to run a marathon, my first marathon might as well be the First Marathon.” Today, on the eve of the 33rd edition, I thought I’d share my impressions from last year as a first-time runner at this major international event, prefaced by a little history (with thanks to Herodotus – see below – for giving us that word).

Where exactly did the idea to stage a race 26.2 miles (or 42, 195 meters) in length come from? You may have heard the story of the great Battle of Marathon in 490 BC between the Athenians and the much greater massed naval power of the Persians (okay, you may have heard of it, but like most of us neither educated in Greece nor at elite British public schools, you probably don’t know anything about it). Against the odds, the Athenians won, and – so the story goes – a messenger ran from the battlefield at Marathon to the Acropolis to announce the great victory, declaring νικῶμεν! (“We won!”) and then, er … expired. Died. Was no more. The problem with this cracking good tale – founding myth of one of the most celebrated events of the modern Olympic games – is that there is virtually no part of that brief story that is in accordance with contemporary sources. Apart, that is, from the fact that the Athenians won.

According to Herodotus, who wrote the first document to be calle History (he literally invented the word), about the Greek – Persian Wars of the early fifth century BC, a certain Pheidippides was a messenger who ran from Athens to Sparta in two days (over approximately 246km of rocky hills – something re-created each September as the Spartathon) in a failed bid to secure Spartan military assistance for the wildly-outnumbered Athenians. Alas the Spartans were in sacred festival mode, and had to decline. Undaunted, he ran back to Athens to inform the rulers that they were on their own.

Herodotus also tells of the victorious Athenian army hot-footing it back to Athens post-victory to prepare anew to fight the crafty Persians, whose fleet had already set sail for Athens from Marathon (perhaps, cunningly, their plan all along). Then there is Plutarch, who tells of an unnamed soldier running from Marathon to Athens to announce the defeat of the Persians. These two (three?) separate events were conflated in the 2nd century AD by Lucian. And Lucian, like Pausanias, says his name was Philippides. However it was Robert Browning, in his 1879 poem ‘Pheidippides’ who attributed to the runner the fate of announcing the Athenian victory, then dying:

‘Rejoice, we conquer!’ Like wine thro’ clay,

Joy in his blood bursting his heart, he died—the bliss!”

This, it turns out, is utter fiction (as admittedly the entire tale might be), a detail Browning added to the ancient sources purely out of what rightly may be termed ‘poetic license’.

However, that isn’t to say that the route from Marathon to downtown Athens is itself wholly fictional. Some number of Greek hoplites, or fleet-footed infantry, did in fact walk, run or stagger back to Athens to defend the city against the Persian fleet if Herodotus is to be believed. It took them longer than the current world record of 02:02:57 – probably more like 7 hours and a bit. But then again they were wearing bronze battle armour, having just fought and defeated the numerically superior Persian forces. And so, as heroic as it may seem for athletes and desk jockeys alike to cover this not-inconsiderable distance, reality for both Pheidippides and his hoplite comrades was in truth a significantly more impressive accomplishment, especially considering the absence in the early 5th century BC of energy gels and ultra lightweight hydration packs. In all likelihood they were barefoot.

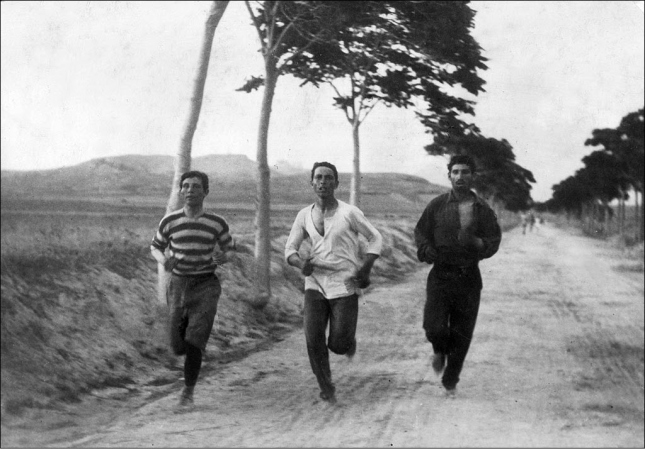

It was at the first modern revival of the Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896, that the idea emerged to hold a race along the route from Marathon to Athens, ending at the newly purpose built stadium known colloquially as Καλλιμάρμαρο / Kallimarmaro, or ‘beautiful marble’. Indeed the stadium sits on the site (and incorporates the remains) of a much larger stadium first used in the ancient Panathenaic Games (ca. 330 BC) reflected in its official name, the Panathenaic Stadium (Παναθηναϊκό στάδιο). This 1896 ‘marathon’ measured a mere 24.8 miles in length. The distance of 26.2 miles was established at the 1908 London Olympics, being the distance from Windsor Castle to the Olympic Stadium at White City.

Back in the day, the road from Marathon to Athens was little more than an unpaved country lane, wending its way through olive groves and vineyards, in a time when Athens itself was a modest city of a mere 123,000 souls. The greater Athens megalopolis is today home to more than 3.7 million. The road trod by Spiridon Louis, the water-carrier who won that first marathon in 1896 and whose name now graces many a running club worldwide, today is a busy highway carrying Athenians to the ferry port of Rafina or their weekend cottages by the sea, past endless gas stations, skyladiko nightclubs, building supply yards and garden ornament dealers. Missing a trick, the 1896 Olympic organisers overlooked the minor detail that the route is uphill for long stretches, thus guaranteeing that Athens Marathon – The Authentic will almost certainly never, ever be the site of a modern world record – something a variety of Mitteleuropen burgs (Berlin, Frankfurt, Zurich, etc.) vie for on the basis of being flat as an eierpfannkuchen and hence places where one can aim to achieve a new ‘personal best’. As world women’s record holder Paula Radcliffe discovered at the 2004 Olympics, the Athens course is daunting even for the world’s best.

But history will only get you so far as motivation to keep putting one foot in front of the other along the grueling, distressingly often uphill 42.195 km slog in temperatures frequently north of 70F (22C). A friend, himself a rather serious runner for whom marathons are merely a warmup for the real challenge of 100 mile ultras over 13,000 foot Colorado mountain passes, told me that of all the races he’d ever run, Athens was his favorite for the simple reason that the public turns out in serious numbers and cheers you on with real pride and gusto, even along some of the most desolate stretches of the course.

And my friend was right. Whatever the route may lack in scenic beauty, the crowds – young and old, athletes and chain smokers alike – are there cheering for the marathonodromoi from the first kilometer right ‘til the end. Yiayias (grannies) dressed head-to-toe in their black mourning dresses shouted words of encouragement – Yera! Kali dynami! Ligo akoma! Dynata! (variations of “Stay strong! Keep going! You’re almost there!”) – children pass out olive branches, hands outstretched to high five every passing runner. Early in the race, it was common to see entire South Asian immigrant families in colorful attire out smiling and cheering by the side of the road, fully sharing in the celebratory spirit of this quintessentially Greek event. Women read your name off your bib and shouted out a personalised ‘Bravo!’ as you plodded through light industrial wasteland and village plateias alike. Even a few police officers cracked a broad smile and applauded. Every few kilometers speakers were set up playing music, blaring everything from infectious laiko folk-pop to the inevitable Zorba the Greek. In one plateia it seemed like half the chorio was out dancing. The atmosphere can only be described as ‘carnival-like’.

Two nights before the big event, AIMS (the Association of International Marathons and Distance Races) – global marathon governing body headquartered in Athens, hosts a dinner and awards ceremony. It is held on the campus of Athens College, an elite private school with American roots for the children of the aspirational management consultant class. Last year, the male and female runners of the year were Dennis Kimetto and Florence Kiplagat, the former having just set the new world record in Berlin a few weeks earlier. Tout Athènes (politicians, television correspondents) were present bedecked in their finery, along with a smattering of foreign runners who, for €50, got to sit through a bewildering number of award presentations followed by a hot buffet supper allegedly formulated as an optimal carbo-loading pre-race repast, but bearing a strong resemblance to wedding catering.

As soon as the presentations were over, many grandees legged it outside for a cigarette (known to Greeks as an ‘athlitikó’) as – befitting a sporting awards gala – the universally-ignored ban on smoking indoors was for once respected. Neither award winner appeared to have been assigned a ‘minder’ and so they were left to fend for themselves, besieged by glitterati wanting them to pose for ‘selfies’. Poor Dennis Kimetto, a young Kenyan subsistence farmer turned distance running phenomenon and world record holder, eventually wandered off alone and unnoticed lugging his sizable boxed trophy, seeking out a quiet spot to sit on a wall behind a tree for a moment’s respite.

The race starts in the modern village of Marathon, in a well-used provincial stadium, its rubber oval track chewed up from years of heavy use and neglect. Runners are bussed from central Athens starting at a little past 5AM for the 25 mile drive along the race route. One entire side of the stadium is lined with dozens of port-a-potties. Everywhere people were wandering around anxiously in their official ‘protection plastic body covers’ (not, in fact, a body-sized condom as a direct translation of the Greek would have suggested, but a re-purposed bin liner as is customary at marathons) trying to stay warm in the pre-7am chill. The only exceptions were a few Orthodox priests, in full black clerical robes … and running shoes. Last year, there were at least a score of elite runners and pacers present from Kenya and Ethiopia, and people stood and watched in amazement as they ran warm-up lap after warm-up lap around the stadium. Bit by bit, people joined in and followed them around the track because running 42,195 meters wasn’t far enough. Seen up close, their effortless gait was something to behold; for a few minutes you had the experience of running alongside world class professional athletes, an opportunity not afforded by any other sport of which I’m aware.

Residents whose homes are near the starting line surely must rue that fact when each year their front gardens become last minute outdoor pissoirs, as runners guzzle bottle after bottle of water, then relieve themselves in the domestic shrubbery before 14,000+ of their fellow participants.

Once underway, the final climb up to the stavrós (crossroad) at Agia Paraskevi takes you through a viaduct reverberating with the sounds of a drum ensemble hammering away on their tom-toms. Both above you and on either side of the road people look down and cheer, in my case some three hours after the race leaders passed by. Your legs feel like lead, and you are barely moving faster than an ambling walking pace, but you realize then that with only the final, downhill stretch to the finish line inside Kallimarmaro, completing the marathon just might be within reach after all.

The weather was perfect that day – perfect for spectating, that is. A cloudless cerulean sky arched overhead, and the course was paved end-to-end in sunshine. The thermometer crept well above 20 degrees C in stark contrast to Frankfurt, where I ran the marathon ten days ago under a sky of solid gray cloud and a marathon-friendly 11 degrees. I made it to Kallimarmaro under my own steam, and then paid my own unintentional homage to the great Pheidippides (quasi-Browning version) collapsing from dehydration about 50 meters past the finish line. A fellow runner spotted me before I hit the deck and I had volunteer medics on me in a flash. An IV was in my arm within minutes and an hour later I strolled out of the medical tent on the stadium infield feeling like I could do the whole thing all over again. Or at least manage to walk home, however gingerly, unaided and upright. The team of medical volunteers were fantastic – they had their hands full thanks to the unseasonably warm weather – and it spoke volumes about their dedication.

As I lay there on the medical cot, a drip re-filling my depleted veins, I had ample opportunity to marvel at and admire how well-managed the entire event had been. Like so much in Greece, its people are singularly capable of accomplishing great things through self-organisation driven by pride, ingenuity and compassion. Parks and beaches, often blanketed in litter that no one seems responsible for collecting, are cleaned regularly by organised volunteer work gangs of civic-minded citizens. The current ongoing work of ordinary citizens in rescuing, aiding, feeding and clothing the thousands of refugees arriving in Lesvos and nearby islands shames the feeble, poorly co-ordinated efforts of official government agencies, the European Union and international aid bodies alike. Athens Marathon – ‘The Authentic’ – is infused from the first mile with the palpable pride of a beleaguered people in commemorating the birth of one of the most extreme athletic challenges ever devised and the history (fictional or otherwise) behind it.

Alas this year there will be no invited (i.e. paid) foreign professional competitors ‘in light of the economic challenges facing the country and its people’. Instead, the organisers ‘invite runners from around the world to run the Athens Marathon in solidarity with the Greek people in this testing time’. Indeed this year, notwithstanding the absence of the international elites, record numbers have signed up to attempt the course. For many a serious distance runner, Athens is on the same ‘must-do’ list as Boston, New York, and London. Over 43,000 are registered to participate in various running events ranging in distance from 5K to the full 42.195 km main event.

And once more I too will be there among the 14,677 registered full marathon runners, shivering in my bin liner, eager to do it all over again.

Images: Colour photos by koutofrangos (2014); black and white photo: Burton Holmes’s “1896 Olympic marathon”. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

[…] In the Footsteps of Pheidippides […]

LikeLike